The East Side Of Baltimore City

Saturday, January 27, 2007

Dominance of Johns Hopkins in the Baltimore Economy

If increasing low service sector wages is to be the engine of a responsible economic development plan, the plan must begin by examining the critical role of the employer that has the most profound impact on Baltimore's private-sector economy: the Johns Hopkins Institutions. As the largest private employer in the state of Maryland, with over 46,00 employees in 2002, the Johns Hopkins Institutions have surpassed and replaced Bethlehem Steel and other manufacturing industries as the economic powerhouse of Baltimore's new economy.

Hopkins' Profitability

According to a report commissioned by Hopkins, the non-profit Johns Hopkins Institutions -- comprised of Johns Hopkins University, the Schools of Medicine, Public Health, Nursing, and other post-graduate institutions, as well as the Johns Hopkins and Health System -- generate over $7 billion in business statewide: one of every 28 dollars in the Maryland economy.

The Hopkins Institutions are among the most "profitable" of all private institutions in Maryland, both non-profit and for-profit. The Hopkins Institutions earned a combined income of over $200 million in the 2002 fiscal year. Their unparalleled renown in research and medical care attracts more grant funding than any other academic institution: $1.4 billion in 2002, more than twice the amount of the second-highest ranking recipient.

From the National Institutes of Health alone, Hopkins received $510 million in 2002, nearly $100 million more than the second-highest recipient [University of Pennsylvania, $418,546,510; University of Washington, $405,729,042; University of California at SF, $365,364,909; Washington University, $343,792,077] of NIH grants.

The Hopkins Institutions also regularly attract the nation's top doctors and medical students, having earned Hopkins Hospital the top spot in US News and World Report's annual hospital rankings for 13 years in a row.

Tax-Exempt Status

The Hopkins Institutions' non-profit status does not come without a cost. As Baltimore struggles with a dwindling tax base, the City's charitable institutions, and Hopkins in particular, generate an ever greater portion of overall income -- and these institutions are exempt from taxes. Within Baltimore City alone, Hopkins Institutions own $505 million worth of tax-exempt property, according to current tax assessments.

Were these properties subject to taxation, Hopkins would have to pay $12 million a year in property taxes to the City. Instead, the burden of paying for schools and other services falls on the rest of Baltimore's residents and businesses.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital

The Johns Hopkins Hospital plays an enormous role in both the Hopkins universe and the local economy. Johns Hopkins Hospital generated over $40 million in net operating income for the system as a whole in 2002, more than double the amount it earned the year before, and its total fund balances (net worth) grew $110 million for the five years ending in fiscal year 2002, to a total of $380 million.

As a non-profit entity, the hospital is obliged to reinvest those earnings in the community which it serves.

In comparison to other hospitals, however, Johns Hopkins Hospital devotes a much smaller percentage of its care to local residents. According to the Hopkins report . . . nearly one quarter of all Johns Hopkins Hospital's total revenue came from out-of-state patients, compared to just 4% at Bayview Medical Center and just over 2% at Howard County General Hospital, both components of the Johns Hopkins Health System.

Indirect Funding: Hidden Subsidies

As noted above, a substantial number of Hopkins Hospital service workers are eligible for public assistance while working full-time at the hospital. Thus public assistance to full-time workers is a hidden government subsidy to the hospital, supplementing the low wages it pays to its service employees. As the chart below shows, Hopkins and other Baltimore hospitals shift the burden of wage payments into the community at large

Shifting the Burden of Low Wages

A Hopkins Hospital environmental service worker who earns an annual income of $20,800 a year ($10/hour) while supporting two children, qualifies for the following public assistance programs:

Public Assistance Program

Annual Cost to Taxpayers

Maryland Child Care and Development Fund

$2,853.37

Federal CCDF expenditures

$8,222.12

Maryland Children's Health Program

$498.00

Baltimore City public Schools Reduced Price Meal Program

$1,222.00

Women, Infants, and Children Program

(if pregnant, nursing, or has an infant child)

$770.25

Total Annual Costs to Taxpayers Per Worker

$13,570.74

America's Leading Hospital Is No Wage Leader

Johns Hopkins Hospital employs far more workers than any other hospital in the City. Including Hopkins Bayview Hospital, Johns Hospital medical institutions account for 35 percent of the city's hospital workforce. [Bon Secours 2%; Maryland General 4%; Harbor 5%; Mercy 6%; Good Samaritan, 7%; St. Agnes 8%; Union Memorial, 8%; Sinai 8%; University of Maryland 11%]

Hopkins thus has the greatest influence over wage rates among Baltimore hospital employers. Yet Hopkins Hospital is not the wage leader among Baltimore hospitals.

[Compared to wages paid by University of Maryland Medical Systems and Prince Georges Hospital Center, Hopkins 2003 Wages comes in 3rd for the positions of Maintenance Mechanic (slightly above $18/hour), Nursing Aide (less than $14/hour), File Clerk (less than $12/hour); Environmental Service Worker ($10/hour); Dietary Aide (less than $10/hour)]

Despite the millions it earns in net income, Johns Hopkins Hospital directs only a small portion of its tax-exempt earnings toward raising the wages of its most poorly paid employees. Despite Hopkins' robust growth and profitability, the wages it pays its employees fall well behind the wages paid to service and maintenance employees at a number of other private Maryland hospitals.

In many job classifications, Hopkins Hospital's average base wage rates rank in the bottom half of all Maryland acute care hospitals. many of the hospitals leading Hopkins in wages are also located in Baltimore, and earn far less in net operating revenue than Johns Hopkins.

Hopkins service and maintenance employee wage policies are clearly independent of the hospital's ability to pay. Hopkins simply chooses not to pay.

The result of that choice is a longstanding wage stagnation for all Baltimore health care workers. Other employers don't have to pay middle-class wages if Johns Hopkins does not.

Higher Wages in Hospitals' Interest

Henry Ford realized early in his career the self-interest employers have in paying their workers fairly: besides providing labor, employees make up much of the industry's consumer base. Ford could not expect to sell cars if his own workers were not paid enough to afford one of their own.

Baltimore's hospitals could learn from this example.

Johns Hopkins, geographically, serves a community with enormous needs for health care services, yet without sufficient means to pay for them.

[Baltimore area residents spent an average of $4,252 on health care, compared to $3,532 for those in the national capital area. Low wage workers, who are heavily concentrated in Baltimore, are far less likely to receive fully-paid health insurance from their employers. Few low-wage workers can afford to pay for private health insurance. . . . The rate of increase of out-of pocket health care expenses for Maryland residents continue to rise -- There are 550,000 Marylanders who are without any form of health insurance.]

Nationwide, predominantly minority minority and low-income neighborhoods such as East Baltimore, where the Hopkins medical campus is located, have some of the highest rates of asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV-related illnesses.

Baltimore area residents already spend more on health care than residents of other regions in Maryland. When they cannot afford health coverage, however, many are either forced to rely on charity care, at great cost to the hospital, or forego care entirely until their situation is dire, at great cost to the entire community.

Better wages would go directly into the community Hopkins serves, resulting in increased utilization of health services, a shift in reliance from emergency facilities to preventive medicine, and a greater number of privately insured patients, improving the hospital's payor mix.

Additionally higher wages decrease employee turnover and cut down on training costs, allowing for a more stable workforce to provide hospital services. Workforce stability is of great importance for patient care. Studies show that patient satisfaction and employee satisfaction at hospitals go hand in hand.

A Matter of Public Policy

Raising hospital workers' wages needs to become more than an issue of employer responsibility to Baltimore. It needs to become a matter of public policy, as well, if only to prevent the further deterioration of the communities in which health industry employers like Johns Hopkins and other hospitals operate.

Bold and visionary leadership is needed to compel trend-setting employers like Johns Hopkins to pay self-sufficiency wages, at the very least, to the workers they employ.

If the influence of such leadership is not brought to bear on Baltimore hospitals, these hospitals and the service sector employers that compete with them for labor will only continue to pay wages so low as to force their employees to rely on public assistance, creating additional burdens for a city that already lacks sufficient resources.

If leading Baltimore hospitals like Johns Hopkins are encouraged to raise their wages to self-sufficient wages levels, the rising incomes and spending power of Baltimore service workers will be harnessed as a major engine of economic growth and development that will contribute to meeting the human needs of Baltimore families, local businesses, and struggling communities of our city.

If increasing low service sector wages is to be the engine of a responsible economic development plan, the plan must begin by examining the critical role of the employer that has the most profound impact on Baltimore's private-sector economy: the Johns Hopkins Institutions. As the largest private employer in the state of Maryland, with over 46,00 employees in 2002, the Johns Hopkins Institutions have surpassed and replaced Bethlehem Steel and other manufacturing industries as the economic powerhouse of Baltimore's new economy.

Hopkins' Profitability

According to a report commissioned by Hopkins, the non-profit Johns Hopkins Institutions -- comprised of Johns Hopkins University, the Schools of Medicine, Public Health, Nursing, and other post-graduate institutions, as well as the Johns Hopkins and Health System -- generate over $7 billion in business statewide: one of every 28 dollars in the Maryland economy.

The Hopkins Institutions are among the most "profitable" of all private institutions in Maryland, both non-profit and for-profit. The Hopkins Institutions earned a combined income of over $200 million in the 2002 fiscal year. Their unparalleled renown in research and medical care attracts more grant funding than any other academic institution: $1.4 billion in 2002, more than twice the amount of the second-highest ranking recipient.

From the National Institutes of Health alone, Hopkins received $510 million in 2002, nearly $100 million more than the second-highest recipient [University of Pennsylvania, $418,546,510; University of Washington, $405,729,042; University of California at SF, $365,364,909; Washington University, $343,792,077] of NIH grants.

The Hopkins Institutions also regularly attract the nation's top doctors and medical students, having earned Hopkins Hospital the top spot in US News and World Report's annual hospital rankings for 13 years in a row.

Tax-Exempt Status

The Hopkins Institutions' non-profit status does not come without a cost. As Baltimore struggles with a dwindling tax base, the City's charitable institutions, and Hopkins in particular, generate an ever greater portion of overall income -- and these institutions are exempt from taxes. Within Baltimore City alone, Hopkins Institutions own $505 million worth of tax-exempt property, according to current tax assessments.

Were these properties subject to taxation, Hopkins would have to pay $12 million a year in property taxes to the City. Instead, the burden of paying for schools and other services falls on the rest of Baltimore's residents and businesses.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital

The Johns Hopkins Hospital plays an enormous role in both the Hopkins universe and the local economy. Johns Hopkins Hospital generated over $40 million in net operating income for the system as a whole in 2002, more than double the amount it earned the year before, and its total fund balances (net worth) grew $110 million for the five years ending in fiscal year 2002, to a total of $380 million.

As a non-profit entity, the hospital is obliged to reinvest those earnings in the community which it serves.

In comparison to other hospitals, however, Johns Hopkins Hospital devotes a much smaller percentage of its care to local residents. According to the Hopkins report . . . nearly one quarter of all Johns Hopkins Hospital's total revenue came from out-of-state patients, compared to just 4% at Bayview Medical Center and just over 2% at Howard County General Hospital, both components of the Johns Hopkins Health System.

Indirect Funding: Hidden Subsidies

As noted above, a substantial number of Hopkins Hospital service workers are eligible for public assistance while working full-time at the hospital. Thus public assistance to full-time workers is a hidden government subsidy to the hospital, supplementing the low wages it pays to its service employees. As the chart below shows, Hopkins and other Baltimore hospitals shift the burden of wage payments into the community at large

Shifting the Burden of Low Wages

A Hopkins Hospital environmental service worker who earns an annual income of $20,800 a year ($10/hour) while supporting two children, qualifies for the following public assistance programs:

Public Assistance Program

Annual Cost to Taxpayers

Maryland Child Care and Development Fund

$2,853.37

Federal CCDF expenditures

$8,222.12

Maryland Children's Health Program

$498.00

Baltimore City public Schools Reduced Price Meal Program

$1,222.00

Women, Infants, and Children Program

(if pregnant, nursing, or has an infant child)

$770.25

Total Annual Costs to Taxpayers Per Worker

$13,570.74

America's Leading Hospital Is No Wage Leader

Johns Hopkins Hospital employs far more workers than any other hospital in the City. Including Hopkins Bayview Hospital, Johns Hospital medical institutions account for 35 percent of the city's hospital workforce. [Bon Secours 2%; Maryland General 4%; Harbor 5%; Mercy 6%; Good Samaritan, 7%; St. Agnes 8%; Union Memorial, 8%; Sinai 8%; University of Maryland 11%]

Hopkins thus has the greatest influence over wage rates among Baltimore hospital employers. Yet Hopkins Hospital is not the wage leader among Baltimore hospitals.

[Compared to wages paid by University of Maryland Medical Systems and Prince Georges Hospital Center, Hopkins 2003 Wages comes in 3rd for the positions of Maintenance Mechanic (slightly above $18/hour), Nursing Aide (less than $14/hour), File Clerk (less than $12/hour); Environmental Service Worker ($10/hour); Dietary Aide (less than $10/hour)]

Despite the millions it earns in net income, Johns Hopkins Hospital directs only a small portion of its tax-exempt earnings toward raising the wages of its most poorly paid employees. Despite Hopkins' robust growth and profitability, the wages it pays its employees fall well behind the wages paid to service and maintenance employees at a number of other private Maryland hospitals.

In many job classifications, Hopkins Hospital's average base wage rates rank in the bottom half of all Maryland acute care hospitals. many of the hospitals leading Hopkins in wages are also located in Baltimore, and earn far less in net operating revenue than Johns Hopkins.

Hopkins service and maintenance employee wage policies are clearly independent of the hospital's ability to pay. Hopkins simply chooses not to pay.

The result of that choice is a longstanding wage stagnation for all Baltimore health care workers. Other employers don't have to pay middle-class wages if Johns Hopkins does not.

Higher Wages in Hospitals' Interest

Henry Ford realized early in his career the self-interest employers have in paying their workers fairly: besides providing labor, employees make up much of the industry's consumer base. Ford could not expect to sell cars if his own workers were not paid enough to afford one of their own.

Baltimore's hospitals could learn from this example.

Johns Hopkins, geographically, serves a community with enormous needs for health care services, yet without sufficient means to pay for them.

[Baltimore area residents spent an average of $4,252 on health care, compared to $3,532 for those in the national capital area. Low wage workers, who are heavily concentrated in Baltimore, are far less likely to receive fully-paid health insurance from their employers. Few low-wage workers can afford to pay for private health insurance. . . . The rate of increase of out-of pocket health care expenses for Maryland residents continue to rise -- There are 550,000 Marylanders who are without any form of health insurance.]

Nationwide, predominantly minority minority and low-income neighborhoods such as East Baltimore, where the Hopkins medical campus is located, have some of the highest rates of asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV-related illnesses.

Baltimore area residents already spend more on health care than residents of other regions in Maryland. When they cannot afford health coverage, however, many are either forced to rely on charity care, at great cost to the hospital, or forego care entirely until their situation is dire, at great cost to the entire community.

Better wages would go directly into the community Hopkins serves, resulting in increased utilization of health services, a shift in reliance from emergency facilities to preventive medicine, and a greater number of privately insured patients, improving the hospital's payor mix.

Additionally higher wages decrease employee turnover and cut down on training costs, allowing for a more stable workforce to provide hospital services. Workforce stability is of great importance for patient care. Studies show that patient satisfaction and employee satisfaction at hospitals go hand in hand.

A Matter of Public Policy

Raising hospital workers' wages needs to become more than an issue of employer responsibility to Baltimore. It needs to become a matter of public policy, as well, if only to prevent the further deterioration of the communities in which health industry employers like Johns Hopkins and other hospitals operate.

Bold and visionary leadership is needed to compel trend-setting employers like Johns Hopkins to pay self-sufficiency wages, at the very least, to the workers they employ.

If the influence of such leadership is not brought to bear on Baltimore hospitals, these hospitals and the service sector employers that compete with them for labor will only continue to pay wages so low as to force their employees to rely on public assistance, creating additional burdens for a city that already lacks sufficient resources.

If leading Baltimore hospitals like Johns Hopkins are encouraged to raise their wages to self-sufficient wages levels, the rising incomes and spending power of Baltimore service workers will be harnessed as a major engine of economic growth and development that will contribute to meeting the human needs of Baltimore families, local businesses, and struggling communities of our city.

Friday, January 26, 2007

Revive Ghetto with Biotech

In the hollowed-out neighborhood known as Middle East, three blocks from the Johns Hopkins University Medical School, La-Z-Boy chairs compete with broken-down Ford pickups for space in vacant lots. Row houses sit empty, their windows cemented. And whether it's 11 a.m. or 11 p.m., a clerk at High-Hat Cut-Rate Liquors sells cigarettes from behind a 5-foot-high wall of bulletproof plastic.

Here, on streets where cardboard signs announce that "drug trafficking or loitering is not permitted in this block anytime," Baltimore is trying to attract a different kind of drug business: biotechnology. Invoking eminent domain, the city will soon evict 250 families and over the next year demolish 300 houses to make way for a 2 million-square-foot office park, wiping out an entire neighborhood in a project reminiscent of 1960s-era slum clearance.

It is a drastic proposal. But when it comes to Middle East, city officials say they have run out of easy options. The only way to save the careworn stretch of 17 blocks, they contend, is to tear it down. Then, they say, the international prestige of Johns Hopkins research laboratories and the immutable laws of the free market will kick in and do for the neighborhood what four decades of urban-revitalization efforts never could: turn it around.

City leaders say the $1 billion biotechnology park will transform the east side of Baltimore into a shiny new corporate Mecca for drug developers, medical-device makers and gene decoders. In 10 years, they say, the park should create 8,000 jobs and 2,000 new and renovated homes. Then scientists will move into new housing, spend their paychecks in the neighborhood and throng to new restaurants, banks and retail shops.

Stakes are high

Many U.S. cities have tried to remake their most troubled neighborhoods with huge reconstruction projects. And dozens of communities around the country have plunged into expensive efforts to court the 25-year-old business of biotechnology, with its promise of cutting-edge science, blockbuster products and economic growth. But Baltimore may be the first to try to do both at the same time.

"The stakes are high for everyone," said Mayor Martin O'Malley, a Democrat. "For the residents, for me politically, for Johns Hopkins. But there really isn't an alternative that makes sense."

Under the plan, homeowners will be given as much as $70,000 in moving costs plus the value of their home, advisers to guide them throughout the move, credit counseling and even rides to inspect potential new homes. Renters will receive the same services and up to five years of rental assistance.

East Baltimore Development, the nonprofit group set up to build the center, says housing built around the biotechnology park will include affordable townhouses and detached homes, meaning that some residents can move back. One-third of the jobs, it says, will be available to those with only a high-school diploma.

Jobs in doubt

So far, there is little organized opposition to the proposal in the predominantly black neighborhood. But there is widespread doubt that the biotechnology center's benefits will ever trickle down to those whose lives will be uprooted to make it possible.

Isaac and Rochelle Jones bought their home on North Wolfe Street 20 years ago when working-class blacks bragged about living in Middle East. In the 12-foot-wide house, they laid white tile in the kitchen and installed central air conditioning, new windows and a baby-blue front door. Today, they have seven years left on a 15-year mortgage.

"I was content to stay in a house that was paid off," said Rochelle Jones, 41, a former state employee disabled by lupus.

She is also concerned about her sons. Antwan, 25, works at Wal-Mart; Maurice, 19, works part time at a Johns Hopkins hospital. Both would like better jobs, but neither attended college.

"If you don't have a college education, you might as well be sweeping the floors," said Isaac Jones, 60, a former factory worker. "You tell me what kind of jobs they can get in biotech."

Best hope

There is little question that Middle East needs help. The blocks of red and white, brick row houses slated for demolition have been plagued by some of the worst violence, unemployment and poverty in the nation. One in four of the houses is vacant. For two decades, the city tried just about everything to clean it up: house-by-house renovations, generous tax credits, stepped-up police patrols.

Nothing worked.

John Shannon Jr., president of East Baltimore Development, said biotechnology is the neighborhood's best hope. The development will be less than two blocks from Johns Hopkins University, a hotbed for the kind of medical research that becomes the basis for biotechnology companies.

In 2001, the university attracted $1.2 billion in research money, the second-biggest sum in the country behind the University of California system, according to the Association of University Technology Managers. Nearby researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, last year attracted $324 million. If there is space in East Baltimore to commercialize the fruits of all that research, the logic goes, biotechnology companies will sprout up. Those, in turn, will support dozens of new businesses.

"The ability to have world-class expertise across the street is very attractive to companies," said Craig Smith, chief executive of Guilford Pharmaceuticals, a Baltimore biotechnology firm.

The city will offer businesses incentives: 10-year credits against property taxes for new construction; one- to three-year tax credits for wages paid to new employees; low-interest loans; and work-force-development grants.

Still, with just a few months left to go before the city sends hundreds of eviction notices, not a single company has committed to building on the site.

Tall order

Shannon concedes that persuading biotechnology executives to put offices in Baltimore's toughest area is a tall order.

Even with Johns Hopkins next door, experts say, East Baltimore will face an uphill battle because of the simple economics of the industry.

The cost of commercializing a biotechnology product is exceedingly high, while the odds of its success are exceedingly low. On average, it takes at least $500 million and 10 years for a biotechnology drug to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration, the goal of every company. Most companies run out of money trying.

"This is a mania," said Joseph Cortright, an economist who has written extensively on the development of biotech centers. "Ten years ago, everyone wanted to be the next Silicon Valley. Three years ago, they wanted to be the center of e-commerce. Now that both of those have fizzled, everyone in the economic-development fraternity thinks they need to be in biotechnology."

In the hollowed-out neighborhood known as Middle East, three blocks from the Johns Hopkins University Medical School, La-Z-Boy chairs compete with broken-down Ford pickups for space in vacant lots. Row houses sit empty, their windows cemented. And whether it's 11 a.m. or 11 p.m., a clerk at High-Hat Cut-Rate Liquors sells cigarettes from behind a 5-foot-high wall of bulletproof plastic.

Here, on streets where cardboard signs announce that "drug trafficking or loitering is not permitted in this block anytime," Baltimore is trying to attract a different kind of drug business: biotechnology. Invoking eminent domain, the city will soon evict 250 families and over the next year demolish 300 houses to make way for a 2 million-square-foot office park, wiping out an entire neighborhood in a project reminiscent of 1960s-era slum clearance.

It is a drastic proposal. But when it comes to Middle East, city officials say they have run out of easy options. The only way to save the careworn stretch of 17 blocks, they contend, is to tear it down. Then, they say, the international prestige of Johns Hopkins research laboratories and the immutable laws of the free market will kick in and do for the neighborhood what four decades of urban-revitalization efforts never could: turn it around.

City leaders say the $1 billion biotechnology park will transform the east side of Baltimore into a shiny new corporate Mecca for drug developers, medical-device makers and gene decoders. In 10 years, they say, the park should create 8,000 jobs and 2,000 new and renovated homes. Then scientists will move into new housing, spend their paychecks in the neighborhood and throng to new restaurants, banks and retail shops.

Stakes are high

Many U.S. cities have tried to remake their most troubled neighborhoods with huge reconstruction projects. And dozens of communities around the country have plunged into expensive efforts to court the 25-year-old business of biotechnology, with its promise of cutting-edge science, blockbuster products and economic growth. But Baltimore may be the first to try to do both at the same time.

"The stakes are high for everyone," said Mayor Martin O'Malley, a Democrat. "For the residents, for me politically, for Johns Hopkins. But there really isn't an alternative that makes sense."

Under the plan, homeowners will be given as much as $70,000 in moving costs plus the value of their home, advisers to guide them throughout the move, credit counseling and even rides to inspect potential new homes. Renters will receive the same services and up to five years of rental assistance.

East Baltimore Development, the nonprofit group set up to build the center, says housing built around the biotechnology park will include affordable townhouses and detached homes, meaning that some residents can move back. One-third of the jobs, it says, will be available to those with only a high-school diploma.

Jobs in doubt

So far, there is little organized opposition to the proposal in the predominantly black neighborhood. But there is widespread doubt that the biotechnology center's benefits will ever trickle down to those whose lives will be uprooted to make it possible.

Isaac and Rochelle Jones bought their home on North Wolfe Street 20 years ago when working-class blacks bragged about living in Middle East. In the 12-foot-wide house, they laid white tile in the kitchen and installed central air conditioning, new windows and a baby-blue front door. Today, they have seven years left on a 15-year mortgage.

"I was content to stay in a house that was paid off," said Rochelle Jones, 41, a former state employee disabled by lupus.

She is also concerned about her sons. Antwan, 25, works at Wal-Mart; Maurice, 19, works part time at a Johns Hopkins hospital. Both would like better jobs, but neither attended college.

"If you don't have a college education, you might as well be sweeping the floors," said Isaac Jones, 60, a former factory worker. "You tell me what kind of jobs they can get in biotech."

Best hope

There is little question that Middle East needs help. The blocks of red and white, brick row houses slated for demolition have been plagued by some of the worst violence, unemployment and poverty in the nation. One in four of the houses is vacant. For two decades, the city tried just about everything to clean it up: house-by-house renovations, generous tax credits, stepped-up police patrols.

Nothing worked.

John Shannon Jr., president of East Baltimore Development, said biotechnology is the neighborhood's best hope. The development will be less than two blocks from Johns Hopkins University, a hotbed for the kind of medical research that becomes the basis for biotechnology companies.

In 2001, the university attracted $1.2 billion in research money, the second-biggest sum in the country behind the University of California system, according to the Association of University Technology Managers. Nearby researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, last year attracted $324 million. If there is space in East Baltimore to commercialize the fruits of all that research, the logic goes, biotechnology companies will sprout up. Those, in turn, will support dozens of new businesses.

"The ability to have world-class expertise across the street is very attractive to companies," said Craig Smith, chief executive of Guilford Pharmaceuticals, a Baltimore biotechnology firm.

The city will offer businesses incentives: 10-year credits against property taxes for new construction; one- to three-year tax credits for wages paid to new employees; low-interest loans; and work-force-development grants.

Still, with just a few months left to go before the city sends hundreds of eviction notices, not a single company has committed to building on the site.

Tall order

Shannon concedes that persuading biotechnology executives to put offices in Baltimore's toughest area is a tall order.

Even with Johns Hopkins next door, experts say, East Baltimore will face an uphill battle because of the simple economics of the industry.

The cost of commercializing a biotechnology product is exceedingly high, while the odds of its success are exceedingly low. On average, it takes at least $500 million and 10 years for a biotechnology drug to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration, the goal of every company. Most companies run out of money trying.

"This is a mania," said Joseph Cortright, an economist who has written extensively on the development of biotech centers. "Ten years ago, everyone wanted to be the next Silicon Valley. Three years ago, they wanted to be the center of e-commerce. Now that both of those have fizzled, everyone in the economic-development fraternity thinks they need to be in biotechnology."

East-Side Biopark spends $60M to acquire properties

The city's effort to revive a low-income East Baltimore neighborhood with new housing and biotechnology companies will grow next year as officials begin to acquire more than 900 properties north of Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Jack Shannon, CEO of East Baltimore Development Inc., the organization leading the east-side project, said the total cost for acquiring properties, relocating families, demolishing buildings and preparing land in the new 57-acre second phase is estimated to be $60 million.

The total project is planned for 88 acres.

Shannon said it will be a challenge to get the needed funding. So far, it has received financial backing from the city, state and federal governments and nonprofits.

"Given the positive momentum we've been able to achieve, along with the overall consensus that we need to continue to advance the work we're doing, we should be able to assemble the necessary resources," Shannon said.

With a biotech building on the 800 block of N. Wolfe Street under construction and expected to be finished by spring 2008, the 31-acre first phase of the project is well under way. Nearly 400 families have been relocated, and hundreds of rowhouses north of Johns Hopkins Hospital have been demolished.

In the project's first phase, homeowners were given an average of $153,000 to compensate for the loss of their home. Officials have pledged that residents of the second phase will get the same level of benefits.

EBDI has spent the past year meeting with neighbors and community groups to develop a plan for the next stage of the project. Shannon estimated that 300 families will be required to move from the neighborhood.

One of those people is Donald Gresham, president of the Save Middle East Action Committee, a neighborhood group representing residents of the area. Gresham, who lives on the 900 block of N. Castle St., said he would like to move into some of the new housing being built, but he worries about whether he will be able to afford to a property and pay increased property taxes.

"My desire is to stay right in the neighborhood," he said.

Gresham said his group is being heard by EBDI. "We are now at the table," he said.

Residents of more than 100 of the 1,040 properties in the second phase will be able to stay in their homes, Shannon said.

The city's effort to revive a low-income East Baltimore neighborhood with new housing and biotechnology companies will grow next year as officials begin to acquire more than 900 properties north of Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Jack Shannon, CEO of East Baltimore Development Inc., the organization leading the east-side project, said the total cost for acquiring properties, relocating families, demolishing buildings and preparing land in the new 57-acre second phase is estimated to be $60 million.

The total project is planned for 88 acres.

Shannon said it will be a challenge to get the needed funding. So far, it has received financial backing from the city, state and federal governments and nonprofits.

"Given the positive momentum we've been able to achieve, along with the overall consensus that we need to continue to advance the work we're doing, we should be able to assemble the necessary resources," Shannon said.

With a biotech building on the 800 block of N. Wolfe Street under construction and expected to be finished by spring 2008, the 31-acre first phase of the project is well under way. Nearly 400 families have been relocated, and hundreds of rowhouses north of Johns Hopkins Hospital have been demolished.

In the project's first phase, homeowners were given an average of $153,000 to compensate for the loss of their home. Officials have pledged that residents of the second phase will get the same level of benefits.

EBDI has spent the past year meeting with neighbors and community groups to develop a plan for the next stage of the project. Shannon estimated that 300 families will be required to move from the neighborhood.

One of those people is Donald Gresham, president of the Save Middle East Action Committee, a neighborhood group representing residents of the area. Gresham, who lives on the 900 block of N. Castle St., said he would like to move into some of the new housing being built, but he worries about whether he will be able to afford to a property and pay increased property taxes.

"My desire is to stay right in the neighborhood," he said.

Gresham said his group is being heard by EBDI. "We are now at the table," he said.

Residents of more than 100 of the 1,040 properties in the second phase will be able to stay in their homes, Shannon said.

Housing at East-Side Biopark

.... As many as 700 new homes are being proposed for a downtrodden section of East Baltimore next to the Johns Hopkins medical campus as part of a $1 billion plan to build a life sciences park there.

That's more than double the minimum of 300 housing units -- a mixture of apartments, townhouses and condominiums -- originally set by planners of the proposed New East Baltimore Community, which is slated to be built in a neighborhood plagued by high crime rates and boarded-up rowhouses.

To accommodate the developers' interest in building housing, the initial phase of the project has been expanded to include 30 acres north of Johns Hopkins Hospital, up from 20 acres. The overall project is designed to be 80 acres.

Each of the three development teams being considered to build the project's $500 million first phase is interested in constructing more than 500 homes as part of the project, said Jack Shannon, president and chief executive officer of East Baltimore Development Inc., the city-affiliated organization overseeing the project. One developer has even proposed more than 700 housing units, he said.

"There is a marketplace for housing north of the Johns Hopkins campus," Shannon said.

The developers believed that more new apartments, condominiums or townhouses could create enough "critical mass" to generate momentum for the neighborhood's turnaround, Shannon said.

Housing could also be attractive to Johns Hopkins graduate students in such fields as medicine, public health and nursing, most of whom live off campus.

Some of the East Baltimore families who are being moved out of the area to clear way for the project may want to move back to the neighborhood when the project is done, Shannon said.

Bill Cassidy, sales manager of the Long & Foster realty office in Fells Point, agreed there will be strong demand for new housing north of the Hopkins campus, especially since nearby Butcher's Hill and Patterson Park are already seeing an influx of new residents who are sprucing up old rowhouses.

"Once the whole area is redone, it will become very much like a new part of the city," he said.

The area north of Hopkins could compete with new suburban townhouse developments because there are always people looking to buy newly constructed homes, Cassidy said.

And the chance to avoid a highway commute to downtown Baltimore could be enticing for many homebuyers.

Spacious townhouses with on-site parking and easy access to the subway could be attractive to buyers who also are looking at small rowhouses with no parking spaces in nearby Canton.

The 11-member EBDI board is now slated to make a decision on a master developer for the overall project sometime in December, a delay from the original goal of mid-November. Shannon said the decision has been delayed because the board wants to do a careful and thorough review of all three proposals.

At first, the project's planners did not know, Shannon said, how big the market would be for housing in the area.

One third of the housing would be sold or rented at market rates. Another third would be designated as affordable housing, with the rest set aside for low-income households. All three proposals include a mix of rental properties and for-sale properties.

One of the three potential lead developers, Steven Grigg, president and chief executive of Washington-based Republic Properties Corp., said the residential part of the project is "probably the most important feature from an urban planning standpoint" because it could have the most impact on the area. He declined to describe his company's proposal in detail.

The other two possible development team leaders are the Washington division of Cleveland-based Forest City Enterprises and a joint venture between Baltimore development firm Struever Bros. Eccles & Rouse Inc. and New Hampshire-based Lyme Properties LLC. Neither could be reached for comment.

The timeline for the initial phase of the project is likely to become clearer when the developer is picked next month.

Johns Hopkins has one graduate student dormitory on the East Baltimore campus, Reed Hall

"We believe that there is some demand for some folks who want to come back to the campus," said Richard Grossi, vice president and chief financial officer of Johns Hopkins Medicine. Additional apartments could help to meet that demand, he said.

Johns Hopkins Medicine has committed to lease 100,000 square feet of office and laboratory space in the life sciences park, Grossi said.

That space is slated for researchers in the medical school's Institute for Basic Biomedical Sciences.

The project's first phase calls for 1 million square feet of office space. Hopkins is playing a role, Grossi said, in trying to recruit companies to the park.

"We've had some people come unsolicited and say, 'Look we're interested in being there,' " said Grossi, who declined to give names. "I'd like a couple of large companies."

That's more than double the minimum of 300 housing units -- a mixture of apartments, townhouses and condominiums -- originally set by planners of the proposed New East Baltimore Community, which is slated to be built in a neighborhood plagued by high crime rates and boarded-up rowhouses.

To accommodate the developers' interest in building housing, the initial phase of the project has been expanded to include 30 acres north of Johns Hopkins Hospital, up from 20 acres. The overall project is designed to be 80 acres.

Each of the three development teams being considered to build the project's $500 million first phase is interested in constructing more than 500 homes as part of the project, said Jack Shannon, president and chief executive officer of East Baltimore Development Inc., the city-affiliated organization overseeing the project. One developer has even proposed more than 700 housing units, he said.

"There is a marketplace for housing north of the Johns Hopkins campus," Shannon said.

The developers believed that more new apartments, condominiums or townhouses could create enough "critical mass" to generate momentum for the neighborhood's turnaround, Shannon said.

Housing could also be attractive to Johns Hopkins graduate students in such fields as medicine, public health and nursing, most of whom live off campus.

Some of the East Baltimore families who are being moved out of the area to clear way for the project may want to move back to the neighborhood when the project is done, Shannon said.

Bill Cassidy, sales manager of the Long & Foster realty office in Fells Point, agreed there will be strong demand for new housing north of the Hopkins campus, especially since nearby Butcher's Hill and Patterson Park are already seeing an influx of new residents who are sprucing up old rowhouses.

"Once the whole area is redone, it will become very much like a new part of the city," he said.

The area north of Hopkins could compete with new suburban townhouse developments because there are always people looking to buy newly constructed homes, Cassidy said.

And the chance to avoid a highway commute to downtown Baltimore could be enticing for many homebuyers.

Spacious townhouses with on-site parking and easy access to the subway could be attractive to buyers who also are looking at small rowhouses with no parking spaces in nearby Canton.

The 11-member EBDI board is now slated to make a decision on a master developer for the overall project sometime in December, a delay from the original goal of mid-November. Shannon said the decision has been delayed because the board wants to do a careful and thorough review of all three proposals.

At first, the project's planners did not know, Shannon said, how big the market would be for housing in the area.

One third of the housing would be sold or rented at market rates. Another third would be designated as affordable housing, with the rest set aside for low-income households. All three proposals include a mix of rental properties and for-sale properties.

One of the three potential lead developers, Steven Grigg, president and chief executive of Washington-based Republic Properties Corp., said the residential part of the project is "probably the most important feature from an urban planning standpoint" because it could have the most impact on the area. He declined to describe his company's proposal in detail.

The other two possible development team leaders are the Washington division of Cleveland-based Forest City Enterprises and a joint venture between Baltimore development firm Struever Bros. Eccles & Rouse Inc. and New Hampshire-based Lyme Properties LLC. Neither could be reached for comment.

The timeline for the initial phase of the project is likely to become clearer when the developer is picked next month.

Johns Hopkins has one graduate student dormitory on the East Baltimore campus, Reed Hall

"We believe that there is some demand for some folks who want to come back to the campus," said Richard Grossi, vice president and chief financial officer of Johns Hopkins Medicine. Additional apartments could help to meet that demand, he said.

Johns Hopkins Medicine has committed to lease 100,000 square feet of office and laboratory space in the life sciences park, Grossi said.

That space is slated for researchers in the medical school's Institute for Basic Biomedical Sciences.

The project's first phase calls for 1 million square feet of office space. Hopkins is playing a role, Grossi said, in trying to recruit companies to the park.

"We've had some people come unsolicited and say, 'Look we're interested in being there,' " said Grossi, who declined to give names. "I'd like a couple of large companies."

Middle East Conflict

By Charles Cohen

Lisa Williams had planned to live in her East Baltimore home for a long time--perhaps even the rest of her life. She and her husband have invested money, emotion, and 18 years of their lives in the house they own on Wolfe Street in this struggling neighborhood, known as Middle East, so she was not pleased when the city approached her in 2000 and told her that she would soon have to move out.

Beginning on Aug. 27, the Baltimore City Council will hold hearings on the long-awaited plan to relocate the residents of Williams' neighborhood to make way for the East Baltimore Biotech Park, a 2 million-square-foot, state-of-the-art, mixed-use development project. The park--a joint effort between the city, the state, the business community, and Johns Hopkins Medical Center--is the linchpin in a plan to redevelop the area around the hospital complex. The park will contain space for emerging biotechnology companies, retail businesses, and mixed-income residences and apartments. If implemented, plan proponents say, the biotech park, its accompanying homes, and supporting businesses could transform Middle East's drug-blighted streets and boarded-up rowhouses into a vibrant planned community. The $1 billion development would be overseen by a nonprofit community redevelopment agency.

In order to put the plan into action, the City Council has but to pass five bills to allow for the condemnation of properties in five different neighborhoods, including Middle East. If the bills are passed by the end of summer, as project proponents anticipate, it will take about 18 months for the city to purchase the homes and begin the first phase of the project. According to Baltimore Deputy Mayor Laurie Schwartz, the first new building projects could be completed by the end of 2003.

But Williams and her neighbors, who say they have been the backbone of a neighborhood which has languished for years, say they want to participate in the creation of a new, prosperous Middle East. After all, Williams says, residents like herself have been the only ones offering the area any kind of stability. But despite a year's worth of city-led presentations designed to inform residents of the east side's bright future, as the time approaches for the city to hold its hearings, Williams and other Middle East residents are becoming more anxious about the city's plans. The city has put together a buyout proposal that will restrict dislocated residents' housing choices. Community members who have invested significantly in their neighborhood also fear that the new Middle East will be beyond their financial means, despite assurances from the city that some of the 2,000 new or rehabbed homes will be "affordable." Schwartz says that the city has yet to set a price for the homes.

"I would love to stay where I'm at and see this redevelopment and live among it," Williams says. Instead, the city plans to move residents from Middle East to other ailing city neighborhoods that need more homeowners as a stabilizing force. But Williams and her neighbors say they don't want to trade one blighted area for another. "We want a decent home in a stable community," she says. "We don't want to move into another area where there are dilapidated homes on each side of where the renovated homes are going to be."

Last Monday evening, two dozen or so of Williams' neighbors gathered in front of a home on Madison Street--one of the last left standing on the a block lined with chainlink fences and scabbed with empty lots--to draw attention to their plight. Above all, they demanded the right to participate in the decision-making process and fair compensation for the loss of their properties.

The city has offered homeowners what it considers a fair deal: Displaced residents will receive the assessed value of their houses, plus moving costs, up to $70,000; residents would be allowed to obtain a $47,500 forgivable mortgage that would be paid off by the city after five years.

But there's a catch: The city will only offer the deal to Middle Easterners who agree to move to other blighted east-side neighborhoods. Residents who choose to move elsewhere will receive less money. For example, those who wish to purchase homes outside of east Baltimore will only be allowed a $27,500 forgivable mortgage.

According to the members of the Save Middle East (Baltimore) Action Committee, however, part of the money being offered to them and their neighbors comes from federal sources that don't allow municipalities to dictate where recipients may live.

On July 12, the group sent a letter to City Council members Paula Branch, Bernard Young, and Pamela Carter objecting to the city's restrictions. "According to the federal housing quality standards . . . the relocatee gets to choose the house he or she desires and therefore determines when a house meets his or her own quality standards," the letter says. "The Federal Relocation Act does not restrict those affected to be bound to specific geographic areas."

Members of the Save Middle East group say that, thus far, their demands to be "treated with respect" by the city have not been met. They say that the first stages of demolition to make way for the park is disrupting their lives (parts of the neighborhood have already been reduced to rubble, and a fine, dusty haze fills the air). They say they want to be able to move to decent neighborhoods, where the quality of life is at least as good as it was in Middle East.

"We haven't even fought the process of a biotech park," says Pat Tracey, the group's president. "What we are saying is, if we have to sacrifice our houses, at least let us choose where we are going to go."

Schwartz says the city is aware of the residents' concerns about the reimbursement deal and is now evaluating its relocation proposal. "There is some question whether it's legal or whether it violates fair-housing laws," she acknowledges, adding that the city is now planning to open an outreach office to give residents a place to voice their concerns and have their questions answered.

Councilperson Branch says she agrees with residents who say they shouldn't be told where to live. As chair of the council's Urban Affairs Committee, she will oversee the council hearings on the project that begin later this month. Branch says residents will have a chance to voice their concerns at the meetings, and that properties that don't need to be demolished to make way for the biotech park will be spared. "If a resident's home is in good condition and up to standard housing code, and they don't want to move, then [the house] will be amended from the bill," Branch says. However, she acknowledges that the Middle East neighborhood--which is situated where the heart of the biotech park is going to be--is going to be difficult to spare.

Despite reassurances, residents feel they are struggling against the political process that is stacked against them and lack advocates in high places.

"It's like we don't have any say because we don't have any money," Williams laments. "They are going to dictate [to us] what they are going to do."

Williams resents the fact that the neighborhood's representatives in the city government seem to be working to have their neighborhood--where she and her neighbors have fought blight and crime for years--rebuilt for someone else.

"This total disrespect for east Baltimore must stop," Tracey shouted through a bullhorn at Monday night's protest. "How do you think this would be done in Roland Park? Would they just roll up the trucks and knock down the buildings?"

"Is this a government for the people, by the people?" asked John Hammock, who had hoped to turn a bakery he owns in the neighborhood into a cooking school for kids. "Are we the people, or is this a joke? I feel like the Indians being put off the reservation."

By Charles Cohen

Lisa Williams had planned to live in her East Baltimore home for a long time--perhaps even the rest of her life. She and her husband have invested money, emotion, and 18 years of their lives in the house they own on Wolfe Street in this struggling neighborhood, known as Middle East, so she was not pleased when the city approached her in 2000 and told her that she would soon have to move out.

Beginning on Aug. 27, the Baltimore City Council will hold hearings on the long-awaited plan to relocate the residents of Williams' neighborhood to make way for the East Baltimore Biotech Park, a 2 million-square-foot, state-of-the-art, mixed-use development project. The park--a joint effort between the city, the state, the business community, and Johns Hopkins Medical Center--is the linchpin in a plan to redevelop the area around the hospital complex. The park will contain space for emerging biotechnology companies, retail businesses, and mixed-income residences and apartments. If implemented, plan proponents say, the biotech park, its accompanying homes, and supporting businesses could transform Middle East's drug-blighted streets and boarded-up rowhouses into a vibrant planned community. The $1 billion development would be overseen by a nonprofit community redevelopment agency.

In order to put the plan into action, the City Council has but to pass five bills to allow for the condemnation of properties in five different neighborhoods, including Middle East. If the bills are passed by the end of summer, as project proponents anticipate, it will take about 18 months for the city to purchase the homes and begin the first phase of the project. According to Baltimore Deputy Mayor Laurie Schwartz, the first new building projects could be completed by the end of 2003.

But Williams and her neighbors, who say they have been the backbone of a neighborhood which has languished for years, say they want to participate in the creation of a new, prosperous Middle East. After all, Williams says, residents like herself have been the only ones offering the area any kind of stability. But despite a year's worth of city-led presentations designed to inform residents of the east side's bright future, as the time approaches for the city to hold its hearings, Williams and other Middle East residents are becoming more anxious about the city's plans. The city has put together a buyout proposal that will restrict dislocated residents' housing choices. Community members who have invested significantly in their neighborhood also fear that the new Middle East will be beyond their financial means, despite assurances from the city that some of the 2,000 new or rehabbed homes will be "affordable." Schwartz says that the city has yet to set a price for the homes.

"I would love to stay where I'm at and see this redevelopment and live among it," Williams says. Instead, the city plans to move residents from Middle East to other ailing city neighborhoods that need more homeowners as a stabilizing force. But Williams and her neighbors say they don't want to trade one blighted area for another. "We want a decent home in a stable community," she says. "We don't want to move into another area where there are dilapidated homes on each side of where the renovated homes are going to be."

Last Monday evening, two dozen or so of Williams' neighbors gathered in front of a home on Madison Street--one of the last left standing on the a block lined with chainlink fences and scabbed with empty lots--to draw attention to their plight. Above all, they demanded the right to participate in the decision-making process and fair compensation for the loss of their properties.

The city has offered homeowners what it considers a fair deal: Displaced residents will receive the assessed value of their houses, plus moving costs, up to $70,000; residents would be allowed to obtain a $47,500 forgivable mortgage that would be paid off by the city after five years.

But there's a catch: The city will only offer the deal to Middle Easterners who agree to move to other blighted east-side neighborhoods. Residents who choose to move elsewhere will receive less money. For example, those who wish to purchase homes outside of east Baltimore will only be allowed a $27,500 forgivable mortgage.

According to the members of the Save Middle East (Baltimore) Action Committee, however, part of the money being offered to them and their neighbors comes from federal sources that don't allow municipalities to dictate where recipients may live.

On July 12, the group sent a letter to City Council members Paula Branch, Bernard Young, and Pamela Carter objecting to the city's restrictions. "According to the federal housing quality standards . . . the relocatee gets to choose the house he or she desires and therefore determines when a house meets his or her own quality standards," the letter says. "The Federal Relocation Act does not restrict those affected to be bound to specific geographic areas."

Members of the Save Middle East group say that, thus far, their demands to be "treated with respect" by the city have not been met. They say that the first stages of demolition to make way for the park is disrupting their lives (parts of the neighborhood have already been reduced to rubble, and a fine, dusty haze fills the air). They say they want to be able to move to decent neighborhoods, where the quality of life is at least as good as it was in Middle East.

"We haven't even fought the process of a biotech park," says Pat Tracey, the group's president. "What we are saying is, if we have to sacrifice our houses, at least let us choose where we are going to go."

Schwartz says the city is aware of the residents' concerns about the reimbursement deal and is now evaluating its relocation proposal. "There is some question whether it's legal or whether it violates fair-housing laws," she acknowledges, adding that the city is now planning to open an outreach office to give residents a place to voice their concerns and have their questions answered.

Councilperson Branch says she agrees with residents who say they shouldn't be told where to live. As chair of the council's Urban Affairs Committee, she will oversee the council hearings on the project that begin later this month. Branch says residents will have a chance to voice their concerns at the meetings, and that properties that don't need to be demolished to make way for the biotech park will be spared. "If a resident's home is in good condition and up to standard housing code, and they don't want to move, then [the house] will be amended from the bill," Branch says. However, she acknowledges that the Middle East neighborhood--which is situated where the heart of the biotech park is going to be--is going to be difficult to spare.

Despite reassurances, residents feel they are struggling against the political process that is stacked against them and lack advocates in high places.

"It's like we don't have any say because we don't have any money," Williams laments. "They are going to dictate [to us] what they are going to do."

Williams resents the fact that the neighborhood's representatives in the city government seem to be working to have their neighborhood--where she and her neighbors have fought blight and crime for years--rebuilt for someone else.

"This total disrespect for east Baltimore must stop," Tracey shouted through a bullhorn at Monday night's protest. "How do you think this would be done in Roland Park? Would they just roll up the trucks and knock down the buildings?"

"Is this a government for the people, by the people?" asked John Hammock, who had hoped to turn a bakery he owns in the neighborhood into a cooking school for kids. "Are we the people, or is this a joke? I feel like the Indians being put off the reservation."

Eastside Development Begins by Chet Dembeck

One of the most blighted sections of the city has taken a giant step toward revitalization.

Federal, state and city officials were all on the same page when they came together Monday to celebrate the groundbreaking of the first of many new buildings being constructed as part of a $1 billion project slated to revitalize a large portion of East Baltimore in the next 10 years.

When completed in 2007, the 282,000-square-foot building at 855 N. Wolfe St. will be the first piece of the Science and Technology Park at Johns Hopkins.

Officials said the 2002 partnership involving the city, state and communities of East Baltimore is beginning to huge pay dividends.

“Johns Hopkins is one of our biggest job generators that we failed to harness in past years,” Mayor Martin O’Malley told The Examiner before the ceremony. “This is a tremendous opportunity for Baltimore’s future.”

Before the project reached it current momentum, the Greater Baltimore Committee raised $1 million to help support East Baltimore Development Inc., the nonprofit that acts as the arm of the partnership, said Donald C. Fry, president of the committee.

Fry said that when completed, the renewal of East Baltimore will act as a catalyst for the rest of the city.

“It’s like dropping a pebble in a pond,” Fry said. “You’ll get a ripple effect.”

Aris Melissaratos, secretary of the Maryland Department of Economic Development, expressed enthusiasm for the project’s potential.

“It is the total rebuilding of an entire community,” he said.

The boundaries of the 80-acre project run from Broadway to Madison Street to Collington Street and the railroad tracks. It was one of the city’s depressed areas with a 56 percent vacancy in some sections, according to city data.

When completed over the next 10 years, the science and technology park will boast 150,000 square feet of office and retail space. It will also include 1,500 new homes for buyers with mixed incomes. Officials estimate the project could generate about 6,000 jobs.

The kinds of jobs the project will generate is particularly important, Joseph Haskins Jr., chairman of East Baltimore Development Inc., told The Examiner.

“This will create opportunities across the board from entry level to highly credentials positions,” he said.

Haskins, who is also the president of The Harbor Bank, said he and others stood steadfast in their hope for transforming the area when others had “written off the neighborhood.”

On Wednesday, The Examiner will explore another project that is breathing new economic life into Baltimore.

Funding for project

» Baltimore: $30 million

» State: $22.5 million

» Federal: $21 million

One of the most blighted sections of the city has taken a giant step toward revitalization.

Federal, state and city officials were all on the same page when they came together Monday to celebrate the groundbreaking of the first of many new buildings being constructed as part of a $1 billion project slated to revitalize a large portion of East Baltimore in the next 10 years.

When completed in 2007, the 282,000-square-foot building at 855 N. Wolfe St. will be the first piece of the Science and Technology Park at Johns Hopkins.

Officials said the 2002 partnership involving the city, state and communities of East Baltimore is beginning to huge pay dividends.

“Johns Hopkins is one of our biggest job generators that we failed to harness in past years,” Mayor Martin O’Malley told The Examiner before the ceremony. “This is a tremendous opportunity for Baltimore’s future.”

Before the project reached it current momentum, the Greater Baltimore Committee raised $1 million to help support East Baltimore Development Inc., the nonprofit that acts as the arm of the partnership, said Donald C. Fry, president of the committee.

Fry said that when completed, the renewal of East Baltimore will act as a catalyst for the rest of the city.

“It’s like dropping a pebble in a pond,” Fry said. “You’ll get a ripple effect.”

Aris Melissaratos, secretary of the Maryland Department of Economic Development, expressed enthusiasm for the project’s potential.

“It is the total rebuilding of an entire community,” he said.

The boundaries of the 80-acre project run from Broadway to Madison Street to Collington Street and the railroad tracks. It was one of the city’s depressed areas with a 56 percent vacancy in some sections, according to city data.

When completed over the next 10 years, the science and technology park will boast 150,000 square feet of office and retail space. It will also include 1,500 new homes for buyers with mixed incomes. Officials estimate the project could generate about 6,000 jobs.

The kinds of jobs the project will generate is particularly important, Joseph Haskins Jr., chairman of East Baltimore Development Inc., told The Examiner.

“This will create opportunities across the board from entry level to highly credentials positions,” he said.

Haskins, who is also the president of The Harbor Bank, said he and others stood steadfast in their hope for transforming the area when others had “written off the neighborhood.”

On Wednesday, The Examiner will explore another project that is breathing new economic life into Baltimore.

Funding for project

» Baltimore: $30 million

» State: $22.5 million

» Federal: $21 million

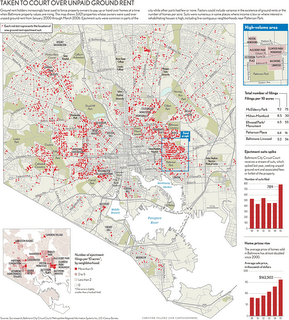

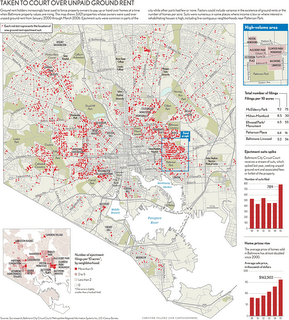

On Shaky Ground

Baltimore's arcane system of ground rents, widely viewed as a harmless vestige of colonial law, is increasingly being used by some investors to seize homes or extract large fees from people who often are ignorant of the loosely regulated process, an investigation by The Sun has found.

Tens of thousands of Baltimore homeowners must pay rent twice a year on the land under their houses. If they fall behind on the payments, the ground rent holders can sue to seize the houses-- and have done so nearly 4,000 times in the past six years, sometimes over back rent as little as $24, The Sun found.

Advertisement

More than half of the ground rent suits filed in the past six years were brought by entities associated with four groups of individuals and families, court records show.

Most ground rent holders insist that home ownership is rarely put in peril. But Baltimore judges awarded houses to ground rent holders at least 521 times between 2000 and the end of March 2006, The Sun found, analyzing court computer data and studying hundreds of case files to document the trend for the first time. The properties ranged from boarded-up rowhouses to a 7,000-square-foot Victorian in Bolton Hill.

In many cases, ground rent holders used their extraordinary power under state law to oust the owners from their houses and then sold the homes for tens of thousands of dollars in profits. Some homeowners reached settlements to regain their houses, paying legal and other fees many times the amount of ground rent owed, though court records don't make clear how often that happens.

While some of the most aggressive investors have owned ground rents for years, it wasn't until the late 1990s that rising property values in Baltimore City made it attractive to attempt to seize houses. The number of new lawsuits rose 73 percent last year and shows no signs of leveling off.

This activity occurs across Baltimore but has clustered in some areas as they have started to gentrify, including neighborhoods just north of Patterson Park and around Washington Village.

Told of The Sun's findings, outgoing Maryland Attorney General J. Joseph Curran Jr. said he had ordered an immediate investigation, adding that it might be time to phase the system out. "An older couple or a widow could forget this, and for someone to come and take their house, when it's worth so much more than they paid for it, is an outrage," Curran said.

The Sun's investigation also found that:

• In nearly every aspect, the law favors ground rent holders. Homeowners rarely win once a lawsuit is filed. And the longer a case goes on, the more it can cost the homeowner.

• No other private debt collectors in Maryland can obtain rewards so disproportionate to what they are owed. In contrast with a foreclosure, the holder of an overdue ground rent can seize a home, sell it and keep every cent of the proceeds. To prevent a seizure, homeowners almost always have to pay fees that dwarf the amount of rent they owe.

• State law puts the onus on property owners to track down their ground rent owner and make payments, though it's sometimes next to impossible to find that information. No registry of ground rent holders exists, and property deeds typically contain only the barest of details about them.

• Some investors seek out overdue ground rents to purchase, then file lawsuits to take the property built on the land. In some cases, the legal owners of these houses have died, and the law is not clear about whether investors must give relatives a chance to satisfy the debts and keep the homes.

'Business is business'

R. Marc Goldberg is a Baltimore attorney and ground rent owner who acts as a spokesman for about two dozen rent holders, including his family and some of the other investor groups that pursue the most ground rent lawsuits, called "ejectments."

He doesn't dispute that clashes over property ownership occur more often these days as investors scramble to reclaim decrepit parts of Baltimore. But he denies that they exploit the ground rent law or charge excessive fees. Nobody gets in trouble if he pays his rent on time, Goldberg said.

"I'm not looking to put people out and to be mean and nasty," he said. In a series of interviews with The Sun, Goldberg repeatedly used the refrain "Business is business."

"I can't deny an economic incentive to make a windfall profit," he said.

Many investors say that while the returns remain attractive, the business is difficult -- with many challenges in collecting the rent or tracking down owners of vacant houses. They say they deserve to be paid their rent on time -- and that they sue to take homes only after lengthy collection efforts, and because it is their only remedy under the law.

"If you don't pay, you are putting your property at risk," said Lawrence Polakoff, a Baltimore Realtor whose family has filed more than 100 ejectment lawsuits since the start of 2000. "A ground rent owner isn't going to just sit back and say, 'I'm sorry someone's died,' and forget about it."

"You can make a very good living doing this," said Polakoff, adding that the increase in ejectment lawsuits is directly related to rising real estate prices.

Most ground rent holders say they rarely, if ever, try to seize homes. For smaller holders, the cost of pursuing an ejectment can be prohibitive. Some investors are fearful of seizing properties that have lead-based paint or housing code violations. Others say they avoid seizures on principle.

Advertisement

"We would never allow ourselves to be in that position. We are about helping people, not hurting them," said Greg Cantori, executive director of the Marion I. and Henry J. Knott Foundation. The foundation, which supports Catholic charities, owns about 1,600 ground rents but hasn't filed an ejectment lawsuit since 1996.

Landlord Baltimore

Estimates of the number of Baltimore properties subjected to ground rent run as high as 120,000, many of them the familiar red-brick and white-marble-stepped rowhouses.

Ground rents take the form of 99-year leases, renewable forever. All property deeds must note whether there is a ground rent. Rents generally range from $24 to $240 a year; some very old leases are written in shillings.

Their origins can be traced to the summer of 1632, when King Charles I of England gave Cecilius Calvert all the land in what is now Maryland. Calvert, better known as the second Lord Baltimore, did what any self-respecting aristocrat did in those days: He charged rent to the colonists who wanted to build on his soil.

Starting in the early 1900s, developers built miles of rowhouses in Baltimore with ground rents. They saw the system as a progressive way to keep home prices within reach of the working class, because people wouldn't have to buy the land as well as the house.

Charities, foundations, churches, banks and some retirees have held ground rents for years as investments. Investors often buy and sell them from each other, sometimes through classified ads.

More recently, some property owners have created new ground rents -- at rates several times higher than the previous rents -- when they sell a property. This is allowed by the law.

Homeowners, however, have the right under state law to buy out ground rents created after 1884 under specified price formulas and conditions.

Though there are residential ground rents in other areas of the state, including Anne Arundel and Baltimore counties, they are far more common in Baltimore City. While unusual, ground rents exist in other places; for example, much of Hawaii has them.

"We view ground rent as one of the sticks in the bundle of property rights," said Carolyn Cook, deputy executive vice president of the Greater Baltimore Board of Realtors, adding, "For the majority of the people, it doesn't have much of an impact."

Loss and gain

Thelma Parks, 56, lived for more than two decades in Druid Heights, just a few blocks from the boyhood home of the late Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, until losing her house last year in an ejectment case. It was filed by a trust set up by Fred Nochumowitz, whose relatives have long held ground rents.

Records show that the Nochumowitz trust bought the ground rent on Parks' house in January 2002. Parks couldn't make her payments, which with the fees for the court action came to "about $1,200," she says. With more time, she says, she could have paid off the $1,200.

After taking her property, the trust sold it to an investment company for $70,000 in September 2005. That company resold it about six months later for $128,000. Parks, meanwhile, was forced to rent in another part of town.

"It ruined every one of my plans," said Parks, who works for the federal government. "They all went out the window. ... I'm going to have to work until I fall apart.

"I can't retire," she said. "Everyone is making a profit from it but me."